Miss-Diagnosed: The Gender Gap in ASD Diagnosis

Kristen Carroll

Illustrations by Michelle Schaffer

Disclaimer: This article uses both identity-first and person-first language surrounding autism spectrum disorder, as well as male and female-gendered language to refer to sex assigned at birth. This choice was made because cited surveys indicate an even split in preference among autistic individuals [1]. Additionally, cited literature uses gendered language to refer to sex assigned at birth. The journal wishes to respect different preferences for person-first versus identity-first language and recognizes that gender is independent of sex assigned at birth.

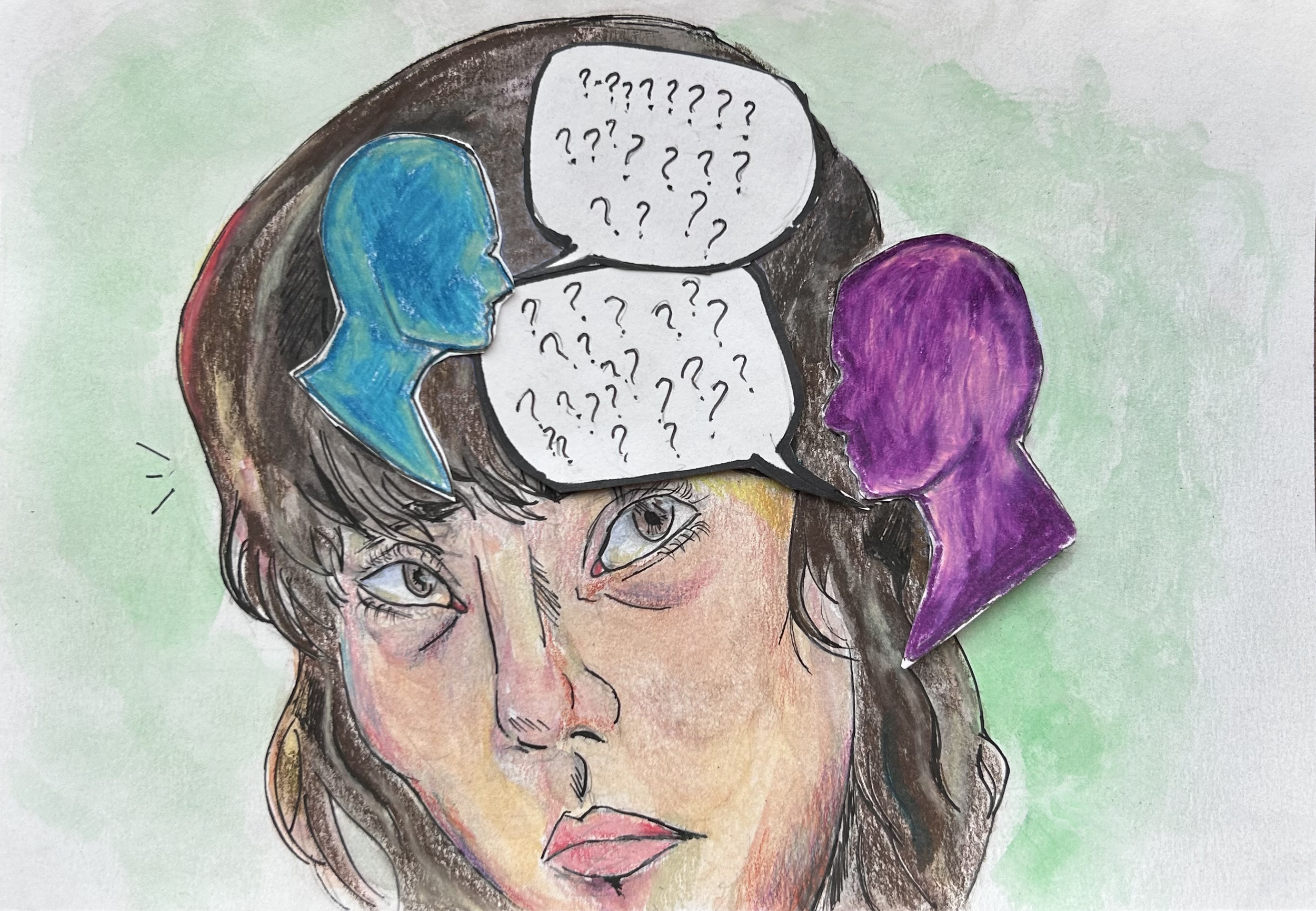

In movies and TV shows like Rain Man and The Good Doctor, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is depicted from the perspective of male characters, portraying their common symptoms as the standard for ASD. Autism spectrum disorder is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by behavioral markers such as differences in communication and sensory processing [2, 3, 4]. Autism exists on a spectrum, with symptoms and needs varying case by case [2, 5, 6]. Representation of autism in the media has brought more attention to the disorder, but not to every aspect of it: the female perspective is often underrepresented. Much like in film and television, the diagnostic criteria for ASD in real life fails to consider how autistic females may present differently than males, leading to misdiagnosis or a complete lack of diagnosis for females [7, 8, 9, 10].

ASD Diagnosis: Then and Now

ASD remained unidentified until Leo Kanner, an Austrian-American psychiatrist, conducted a study on the disorder in 1938 [11]. In his investigation, Kanner considered the traits of eleven young children: eight males and three females. After studying the children’s common behaviors, speech, and motor development, Kanner conceptualized a new disorder called autism [11]. Despite his significant contribution to our understanding of autism, Kanner’s study was flawed due to its small and skewed sample. The bias towards male populations in ASD research continues to hinder the ability of autistic females to receive diagnoses today, as the traits females display are often inconsistent with the traits displayed by autistic males [7, 8, 9, 10]. ASD has become more common in recent years, with an estimated 75-fold increase in the rate of ASD diagnosis over a twenty-year period [12]. Despite its increasing prevalence in society, the ratio of male to female ASD diagnoses has remained relatively stable; for every three to four males with ASD, only one female is diagnosed [10].

An ASD diagnosis can be beneficial or even life-changing for a person with autism, as a diagnosis opens up doors for additional support to improve well-being [13]. Once diagnosed, doctors can offer patients various tools to improve their quality of life, including mental health services and accommodations to navigate education services better. Education accommodations include extended time for testing, flexible deadlines, and distraction-free test zones [13]. Unfortunately, these accommodations are not accessible to everyone, especially those who don’t receive an official diagnosis. Since diagnostic criteria for autism are heavily influenced by the common signs and symptoms found in males, autistic females are less likely to be diagnosed than males, preventing them from receiving proper interventions [7, 8, 9, 10].

Checking Out The Checklist

To be diagnosed with ASD, a person must meet specific diagnostic criteria early in life, including communication difficulties, social impairment, and restrictive, repetitive behaviors and interests [14]. The first criterion to be diagnosed with ASD is that individuals must show multiple deficits in their social interactions. Examples may include difficulty interpreting nonverbal social cues and maintaining friendships, struggling with verbal communication, or having trouble understanding the feelings and needs of others. Signs and symptoms typically become evident in late infancy as communication skills develop and become essential to navigating social interactions. A second criterion for diagnosis is that one must have restrictive and repetitive behaviors and interests (RRBIs) [14]. Common restrictive patterns include strong attachments to a limited range of activities or interests, such as continuously listening to the same song or following the same schedule daily [15]. Repetitive patterns can also include body movements such as flapping one’s hands or rocking back and forth, a behavior classified as ‘stimming’ [16]. Autistic people perform ‘stimming’ — either consciously or unconsciously — in an attempt to regulate their emotions [16]. Altogether, these symptoms must significantly impede a person’s daily functioning for them to receive an ASD diagnosis [14].

Society is shaped around neurotypical individuals — whose needs often differ from autistic individuals — and so daily activities like attending class or socializing with others can be exhausting for people with autism [17, 18]. An autistic person who has difficulty communicating with peers or managing sensory stimuli can become overwhelmed at school or work, leading to involuntary emotional and physical reactions characterized as ‘meltdowns’ [19]. Picture each daily task or stressor as one shake of a Coca-Cola can. As stress and anxiety build up throughout the day, causing more and more shakes of the can, the pressure builds up. Eventually, the can explodes. In an autistic individual, this explosion is known as a ‘meltdown’ [19]. Beyond communication, social, and other behavioral criteria, an autism diagnosis requires a physician’s documentation of symptoms in early childhood [14]. However, autistic people are often not assessed for the disorder as children, which can lead to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis, both of which frequently delay one’s ability to receive treatment [20]. Support from schools or doctors falls short when an autistic individual does not have an official ASD diagnosis. Furthermore, both underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis are thought to be more prevalent in autistic females than in autistic males during their first psychiatric evaluations because present-day criteria do not account for autistic females’ symptoms [20, 21].

Why do Autistic Females Fall Through the Cracks?

Like Kanner’s first study on ASD, later studies on behavioral markers of autism predominantly recruited males [22, 11, 32, 7, 10, 8]. However, females with ASD often present with different traits than autistic males [24]. For example, autistic females often exhibit different restrictive and repetitive behaviors and interests (RRBIs) than autistic males [25]. Autistic individuals tend to have specific interests, sometimes termed ‘restricted interests,’ that are repetitive or limited to a narrow range that holds the individual’s attention [26]. Autistic males’ restricted interests tend to be in math, science, sports, and technology, which are more stereotypically associated with autism. However, autistic females usually have restricted interests in different categories, such as dancing, music, arts and crafts, and fantasy tales [27, 28, 29, 25]. As a result, behaviors can fly under the radar of teachers, parents, and even doctors [24, 27]. Females, therefore, do not appear to meet the criterion for RRBIs, leading to a decrease in diagnosis for autistic females [25].

Another way autistic females often differ in presentation from autistic males is through their social relationships [24]. Females with autism often exhibit a higher social motivation and a stronger inclination towards forming social connections than males with autism. They usually have a stronger desire to develop friendships, potentially making them appear more neurotypical [24]. As a result, autistic females are less likely to meet the social impairment criterion, which can reduce their likelihood of receiving an autism diagnosis. While autistic females often seek social interactions, they frequently find these interactions strenuous because they try to reduce their expression of autistic traits through a behavior known as ‘masking’ [24, 30]. ‘Masking’ entails forcing oneself to maintain eye contact, mimic facial expressions, and create a ‘script’ for social situations [24]. The motivation to mask can stem from a desire to fit in with neurotypical society to avoid rejection, discrimination, or bullying [30, 31]. Autistic females exhibit this behavior more often than autistic males, which may be the result of societal pressure stemming from common gender norms [24, 32, 34, 35]. For example, females are often perceived as more extroverted than males and, as a result, are expected to thrive in social situations [32]. Therefore, autistic females are forced to mask more often, disguising autistic traits and further contributing to underdiagnosis [32].

Closing the Gap in ASD Diagnosis

Despite differences in the presentation of autism spectrum disorder between males and females, the diagnostic criteria are based predominantly on the male presentation, thereby excluding females [24]. Symptoms observed in autistic females often do not align with the established criteria, leading to a delay in or lack of diagnosis [25, 8, 24]. Delayed diagnoses can lead to delayed care and, subsequently, more difficulties experienced by autistic people [36, 37]. Without a timely diagnosis, autistic individuals are less likely to receive early intervention, an approach starting from early childhood that has been shown to improve ASD-related symptoms [38]. Receiving early intervention can help to mitigate difficulties faced by individuals with ASD sooner [38]. Increasing funding to ensure females are included in research and redefining current diagnostic criteria may eventually close this gap between the sexes, improving the rates of accurate diagnosis and the quality of life for autistic females [8, 39].

References

Taboas, A., Doepke, K., & Zimmerman, C. (2023). Preferences for identity-first versus person-first language in a US sample of autism stakeholders. Autism: the international journal of research and practice, 27(2), 565–570. doi: 10.1177/13623613221130845

Cremone-Caira, A., Braverman, Y., MacNaughton, G. A., Nikolaeva, J. I., & Faja, S. (2023). Reduced visual evoked potential amplitude in autistic children with co-occurring features of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. doi: 10.1007/s10803-023-06005-7

Hodges, H., Fealko, C., & Soares, N. (2020). Autism spectrum disorder: definition, epidemiology, causes, and clinical evaluation. Translational Pediatrics, 9(1), S55–S65. doi: 10.21037/tp.2019.09.09

Khaledi, H., Aghaz, A., Mohammadi, A., Dadgar, H., & Meftahi, G. H. (2022). The relationship between communication skills, sensory difficulties, and anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder. Middle East Current Psychiatry, 29(1). doi: 10.1186/s43045-022-00236-7

Alpert, J. S. (2020). Autism: a spectrum disease. The American Journal of Medicine, 134(6), 701–702. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.10.022

Huang, C., Chen, K. C., Lee, G.-Y., Chia Wei Lin, & Chen, K. (2023). Different autism measures targeting different severity levels in children with autism spectrum disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. doi: 10.1007/s00406-023-01673-z

de Giambattista, C., Ventura, P., Trerotoli, P., Margari, F., & Margari, L. (2021). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: focus on high functioning children and adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.539835

Belcher, H. L., Morein-Zamir, S., Stagg, S. D., & Ford, R. M. (2022). Shining a light on a hidden population: social functioning and mental health in women reporting autistic traits but lacking diagnosis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05583-2

Fusar-Poli, L., Brondino, N., Politi, P., & Aguglia, E. (2020). Missed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of adults with autism spectrum disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 272(2). doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01189-w

Wu Nordahl, C. (2023). Why do we need sex‐balanced studies of autism? Autism Research, 16(9), 1662–1669. doi: 10.1002/aur.2971

Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child: Journal of Psychopathology, Psychotherapy, Mental Hygiene, and Guidance of the Child, 2 217–50.

Watkins, L. V., & Angus-Leppan, H. (2022). Increasing incidence of autism spectrum disorder: are we over-diagnosing? Advances in Autism, 9(1). doi: 10.1108/aia-10-2021-0041

Sarrett, J. C. (2017). Autism and accommodations in higher education: insights from the autism community. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(3), 679–693. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3353-4

Mottron, L. & Gagnon, D. (2023). Prototypical autism: new diagnostic criteria and asymmetrical bifurcation model. Acta Psychologica, 237, 103938–103938. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.103938

Ravizza, S. M., Solomon, M., Ivry, R. B., & Carter, C. S. (2017). Restricted and repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders: the relationship of attention and motor deficits. Development and Psychopathology, 25(3), 773–784. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000163

Charlton, R. A., Entecott, T., Belova, E., & Nwaordu, G. (2021). “It feels like holding back something you need to say”: Autistic and non-autistic adults' accounts of sensory experiences and stimming. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 89(89), 101864. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101864

Black, M. H., Clarke, P. J. F., Deane, E., Smith, D., Wiltshire, G., Yates, E., Lawson, W. B., & Chen, N. T. M. (2023). “That impending dread sort of feeling”: Experiences of social interaction from the perspectives of autistic adults. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 101, 102090. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2022.102090

Mantzalas, J., Richdale, A. L., Adikari, A., Lowe, J., & Dissanayake, C. (2021). What is autistic burnout? A thematic analysis of posts on two online platforms. Autism in Adulthood, 4(1). doi: 10.1089/aut.2021.0021

Bedrossian, L. (2015). Understand autism meltdowns and share strategies to minimize, manage occurrences. Disability Compliance for Higher Education, 20(7), 6–6. doi: 10.1002/dhe.30026

Ghanouni, P. & Seaker, L. (2023). What does receiving autism diagnosis in adulthood look like? Stakeholders’ experiences and inputs. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 17(1). doi: 10.1186/s13033-023-00587-6

Gesi, C., Migliarese, G., Torriero, S., Capellazzi, M., Omboni, A. C., Cerveri, G., & Mencacci, C. (2021). Gender differences in misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis among adults with autism spectrum disorder with no language or intellectual disability. Brain Sciences, 11(7), 912. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11070912

Young, H., Oreve, M. J., & Speranza, M. (2018). Clinical characteristics and problems diagnosing autism spectrum disorder in girls. Archives de Pédiatrie, 25(6), 399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2018.06.008

Ratto, A. B., Kenworthy, L., Yerys, B. E., Bascom, J., Wieckowski, A. T., White, S. W., Wallace, G. L., Pugliese, C., Schultz, R. T., Ollendick, T. H., Scarpa, A., Seese, S., Register-Brown, K., Martin, A., & Anthony, L. G. (2018). What about the girls? Sex-based differences in autistic traits and adaptive skills. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(5), 1698–1711. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3413-9

Hull, L., Petrides, K.V. & Mandy, W. (2020). The female autism phenotype and camouflaging: a narrative review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 7, 306–317. doi: 10.1007/s40489-020-00197-9

Antezana, L., Factor, R. S., Condy, E. E., Strege, M. V., Scarpa, A., & Richey, J. A. (2018). Gender differences in restricted and repetitive behaviors and interests in youth with autism. Autism Research, 12(2), 274–283. doi: 10.1002/aur.2049

Kimhi, Y. (2013). Restricted Interest. In: Volkmar, F.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders. Springer, New York, NY. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3_102

Sutherland, R., Hodge, A., Bruck, S., Costley, D., & Klieve, H. (2017). Parent-reported differences between school-aged girls and boys on the autism spectrum. Autism, 21(6), 785–794. doi: 10.1177/1362361316668653

McFayden, T. C., Albright, J., Muskett, A.E., Scarpa. (2019). Brief report: sex differences in asd diagnosis—a brief report on restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. J Autism Dev Disord 49, 1693–1699. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3838-9

Grove, R., Hoekstra, R. A., Wierda, M., & Begeer, S. (2018). Special interests and subjective wellbeing in autistic adults. Autism Research, 11(5), 766–775. doi: 10.1002/aur.1931

Chapman, L., Rose, K., Hull, L., & Mandy, W. (2022). “I want to fit in… but I don’t want to change myself fundamentally”: A qualitative exploration of the relationship between masking and mental health for autistic teenagers. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 99, 102069. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2022.102069

Hull, L., Petrides, K.V., Allison, C., Smith, P., Baron-Cohen, S., Lai, M., Mandy, W. (2017). “Putting on my best normal”: social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. J Autism Dev Disord 47, 2519–2534. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5

Schuck, R.K., Flores, R.E. & Fung, L.K. (2019). Brief report: sex/gender differences in symptomatology and camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 49, 2597–2604. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03998-y

Simcoe, S. M., Gilmour, J., Garnett, M. S., Attwood, T., Donovan, C., & Kelly, A. B. (2022). Are there gender-based variations in the presentation of autism amongst female and male children? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05552-9

Milner, V., Colvert, E., Mandy, W., & Happé, F. (2022). A comparison of self‐report and discrepancy measures of camouflaging: exploring sex differences in diagnosed autistic versus high autistic trait young adults. Autism Research. doi: 10.1002/aur.2873

Alaghband-rad, J., Hajikarim-Hamedani, A., & Motamed, M. (2023). Camouflage and masking behavior in adult autism. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1108110

Wergeland, G. J. H., Posserud, M.-B., Fjermestad, K., Njardvik, U., & Öst, L.-G. (2022). Early behavioral interventions for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder in routine clinical care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 29(4). doi: 10.1037/cps0000106

Højslev, A. S., Thomsen, P. H., Schendel, D., Jørgensen Meta, Carlsen, A. H., & Loa, C. (2021). Factors associated with a delayed autism spectrum disorder diagnosis in children previously assessed on suspicion of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(11), 3843-3856. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04849-x

Landa, R. J. (2018). Efficacy of early interventions for infants and young children with, and at risk for, autism spectrum disorders. International Review of Psychiatry, 30(1), 25–39. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1432574

D’Mello, A. M., Frosch, I. R., Li, C. E., Cardinaux, A. L., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2022). Exclusion of females in autism research: empirical evidence for a “leaky” recruitment‐to‐research pipeline. Autism Research, 15(10). doi: 10.1002/aur.2795