Love on the Brain: The Science of Lust, Attraction, and Attachment

Elsie McKendry

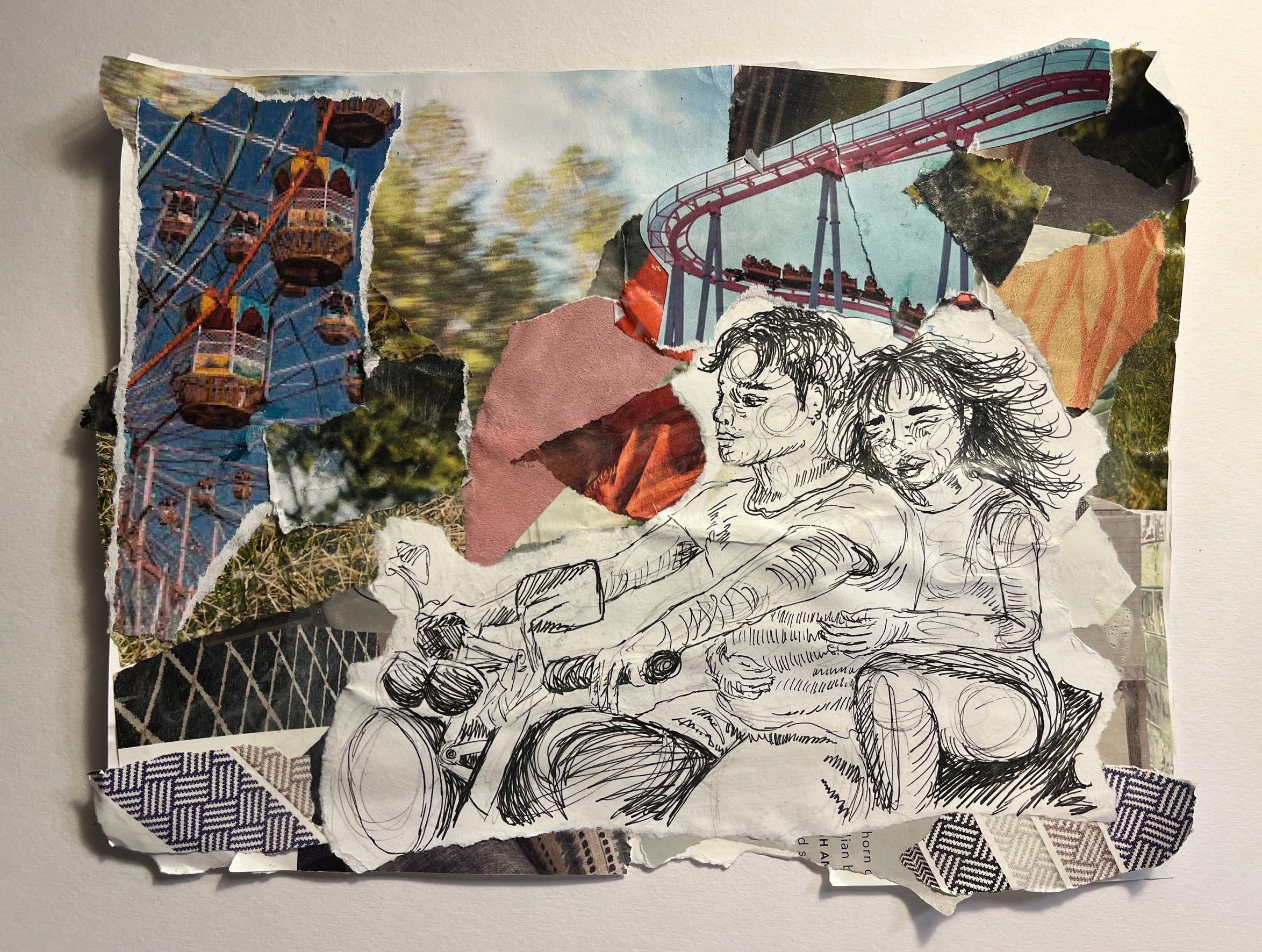

Illustrations by Abby Schoenecker

“Thus with a kiss I die,” proclaimed Romeo, standing over Juliet’s still body. In Romeo and Juliet, playwright William Shakespeare writes of a love so powerful that it drives a man to suicide. Similar testaments to the power of love can be found across time and cultures, in poetry, music and the tradition of marriage itself. In many ways, love is inexplicable, rendering attempts to define it difficult. ‘Love’ is commonly used as a general term to encapsulate everything ranging from sexual attraction and crushes to deep romantic love. While feelings of lust, attraction, and attachment are often experienced simultaneously, they can exist separately as well. For instance, the love shared between a parent and child demonstrates the separation of attachment from attraction and lust. Alternatively, you may be in love with a long-term partner while still feeling attraction to another person or celebrity crush. Studying the complex distinctions between lust, attraction, and attachment from a neuroscience perspective can help explain why love makes humans feel and act the way we do.

Lust: I Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You

Two college students, Rohan and Charlotte, are at a party. As Rohan watches Charlotte dancing across the room, he wants to be close to her and wanders over to join. While dancing with Charlotte, Rohan notices his growing excitement manifested by her touch and can’t stop thinking about kissing her. He begins to lose self-awareness and feels tempted to act on his impulses. Rohan is enveloped by feelings of lust, a state of sexual arousal characterized by physiological responses that encourage physical intimacy and reproduction [1]. In this moment, Rohan’s passionate reaction can be understood in part by looking at the brain.

Lust is controlled by multiple changes in the brain, including reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex and increased hormone production triggered by the hypothalamus [2]. The prefrontal cortex mediates complex cognitive behaviors, especially those concerning the ability to suppress urges that may lead to socially unacceptable behaviors [2, 3]. The hypothalamus is a part of the brain that regulates key bodily functions, such as the regulation of sexual drives [4]. Feelings of sexual arousal are elicited when the hypothalamus signals the reproductive system to release sex hormones called testosterone and estrogen [5]. These hormones increase sex drive which in turn helps facilitate genital lubrication and increased genital sensory perception [5, 6]. High levels of estrogen and testosterone also promote the release of dopamine, a chemical messenger active in the brain’s reward system that is crucial for the perception of pleasure in romantic and sexual contexts [16]. These functions make Charlotte and Rohan more receptive to and stimulated by sexual activity. Since sexual arousal is pleasurable, Rohan and Charlotte feel motivated to later return to this physiological state. Other than hormone production, the inhibition of activity within the prefrontal cortex facilitates sexual activity [2]. Periods of high sexual arousal are associated with suppression of activity in the prefrontal cortex, the portion of the brain responsible for decision making [7]. A lack of prefrontal cortex activity is associated with behaviors such as getting caught up in the moment, the dissolution of usual physical boundaries, and a loss of control [2]. For this reason, Rohan and Charlotte may lose self-awareness and act on impulse, rather than thinking about the potential outcomes of their actions.

Attraction: I Want to Hold You

A week after meeting at the party, Rohan and Charlotte decide to visit an amusement park together. As Charlotte and Rohan walk through the crowds, Charlotte feels jittery with excitement. Her heart beats quickly, and her palms start to sweat; these symptoms are characteristic of the ‘fight or flight’ response, caused by the sympathetic nervous system, which mediates bodily functions through a network of nerves that are ‘excited’ by being in close proximity to one’s crush. [8]. Attraction, otherwise known as passionate love, refers to the feelings of intense infatuation often present during the formation of relationships, and is known to trigger the sympathetic nervous system [8]. Although love isn’t usually a source of danger, it leads to an arousal state that parallels the physiological effects of fear and excitement. Conversely, these danger responses may also prompt feelings of attraction. In situations where acute stress is external and unrelated to attraction, like when about to ride a rollercoaster, the activation of a person’s fight or flight response may cause the misinterpretation of fear-based arousal as attraction [9, 10]. Therefore, during their second date, Charlotte may find Rohan more attractive than she would have otherwise because she misinterprets her amusement park-induced state as romantic attraction [10]. While extreme stress inhibits attraction, stress in small doses can actually enhance it [9]. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system can cause short-term increases in testosterone, thus increasing sexual desire [5, 11]. Emotional connections can also be enhanced by the release of cortisol, a primary stress hormone associated with the formation of social attachment [12].

In addition to physiological arousal, compulsive thinking and intense desire for proximity to another person are characteristics of attraction [13]. In the days following their date, Charlotte replays her experience with Rohan over and over in her mind. She finds herself distracted in class and unable to sleep, obsessively thinking about the next time she will see Rohan. Dopamine, one of the chemical messengers involved in lust, is partially responsible for Charlotte’s obsessive reaction [14]. Dopamine plays a significant role in the brain’s reward center and reinforces sex-related stimuli by rewarding a person with a ‘high’ when they are interacting with their crush [13]. Charlotte may even begin to feel ‘lovesick,’ as elevated levels of dopamine are associated with feelings of ecstasy, increased energy, sleeplessness, reduced appetite, and anxiety [13]. Moreover, these chemical changes in the brain lead to focused attention on a person, their positive traits, past memories with them, and the sense that they are unique [1].

Attachment: Now That I’ve Found You, Stay

After a year of dating, Rohan and Charlotte’s relationship has evolved. The anxious butterflies Rohan feels in Charlotte’s presence are replaced by a sense of security. As the boundaries between them dissolve, they can be vulnerable with each other without fear of judgment. This stable and secure state is also referred to as attachment and is characteristic of long-term relationships, marriage, committed friendships, and parent-child relationships [16, 17]. Attachment includes the same desire for proximity and physical contact present in attraction, but it is generally perceived as less urgent [16]. This transition from attraction to attachment is sometimes interpreted as the end of the ‘honeymoon phase’ [18]. As Rohan and Charlotte lay in bed cuddling at night, the release of oxytocin in their bodies contributes to the sense of calmness they feel. Oxytocin is a hormone associated with positive social behavior such as pair bonding, sexual activity, and parental behaviors [19]. The relaxation and safety present in attachment is facilitated by the parasympathetic nervous system [20]. This system works in opposition to the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the stress and excitement associated with attraction. The parasympathetic nervous system is regulated by oxytocin, which reduces stress through the inhibition of our fear response [19]. In other words, attraction can be enhanced by the body’s stress response while attachment inhibits those anxieties.

In addition to its role in the parasympathetic nervous system, oxytocin is associated with processing and retention of social cues [13]. For instance, Rohan’s attachment to Charlotte makes him very perceptive of subtle changes in Charlotte's behavior and mood that may go undetected by others. This attachment between Rohan and Charlotte is similar to attraction due to the increased presence of dopamine in both stages. Specifically, the differences in activation of the brain regions which play distinct roles in the facilitation of attraction and attachment, like the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), are modified over the course of this transition between attraction and attachment. The dACC helps process information and facilitates decision making based on the context of social interactions [20]. The PCC contributes to increased social awareness and trustworthiness in the progression of romantic love [21, 22]. During the attraction phase often present in short relationships (one to seven months), activity in the dACC and PCC is low. As a relationship transitions to the attachment stage (eight to seventeen months), increased activation in the dACC and PCC is associated with the suppression of obsessive thinking [23]. These anxious tendencies disappear around six months after initially falling in love; therefore, alterations in dACC and PCC activation may help explain these changes [13].

Lust, Attraction, and Attachment: I Want to Know What Love Is

Although they all exist as forms of love, lust, attraction, and attachment each possess their own qualities and serve different functions. For instance, lust is primarily associated with the initiation of sexual activity through hormone production and reduced activity of the prefrontal cortex. Attraction, on the other hand, motivates infatuation with a person via the sympathetic nervous system and the release of dopamine. These stages precede attachment, which characterizes secure commitment to a significant other due to the parasympathetic nervous system, the release of oxytocin, and activation in the dACC and PCC.

Charlotte and Rohan experience lust, attraction, and attachment together; however, these three systems can exist independently from one another as well. For instance, Charlotte finds her local barista handsome, yet has no emotional attachment to him. On the other hand, Charlotte may feel attachment towards her best friend without feeling sexual attraction towards her [24]. If lust, attraction, and attachment can be functionally independent, why do they so often occur simultaneously? Attachments are most likely to form between individuals that have extensive contact with one another over prolonged periods of time [16]. Lust and attraction provide grounds for this extended contact, increasing the likelihood that one becomes emotionally attached to sexual partners [16]. Not to mention, sex can be a means of expressing attachment to one’s partner, as physical intimacy releases oxytocin and can aid the development of emotional connection [8].

More broadly speaking, social beliefs about romantic relationships may help explain why we fall in love with the people we are sexually attracted to. People may believe that lust, attraction, and attachment all exist together under the umbrella concept of ‘love’ [25]. This assumption may be connected to the social importance of finding a lifelong romantic partner and the ostracization of those who decide to stay single or refuse to commit to a single partner [26]. Such interactions between neurological and social mechanisms contribute to the complexity of human relationships and our conception of love as a whole.

References

Fisher, E. E., Aron, A., Mashek, D., Haifang, L., & Brown, L. L. (2002). Defining the brain systems of lust, romantic attraction, and attachment. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31(5), 413-419. doi:10.1023/A:1019888024255.

Georgiadis, J. R. (2012). Doing it … wild? on the role of the cerebral cortex in human sexual activity. Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology, 2(1), 17337. doi:10.3402/snp.v2i0.17337.

Calabrò, R. S., Cacciola, A., Bruschetta, D., Milardi, D., Quattrini, F., Sciarrone, F., Rosa, G., Bramanti, P., & Anastasi, G. (2019). Neuroanatomy and function of human sexual behavior: A neglected or unknown issue? Brain and Behavior, 9(12). doi:10.1002/brb3.1389.

Saper, C. B., & Lowell, B. B. (2014). The hypothalamus. Current Biology, 24(23), 1111-1116. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.023.

Graziottin, A. (2000). Libido: The biologic scenario. Maturitas, 34. doi:10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00072-9.

Seshadri, K. G. (2016). The neuroendocrinology of Love. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 20(4), 558. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.183479.

Forbes, C. E., & Grafman, J. (2010). The role of the human prefrontal cortex in social cognition and moral judgment. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 33(1), 299–324. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153230.

Fisher, H., Aron, A., & Brown, L. L. (2005). Romantic love: An fmri study of a neural mechanism for mate choice. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 493(1), 58–62. doi:10.1002/cne.20772.

Finke, J. B., Behrje, A., & Schächinger, H. (2018). Acute stress enhances pupillary responses to erotic nudes: Evidence for differential effects of sympathetic activation and cortisol. Biological Psychology, 137, 73–82. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.07.005.

Jouffre, S. (2014). Power modulates over-reliance on false cardiac arousal when judging target attractiveness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(1), 116–126. doi:10.1177/0146167214559718.

AlAwlaqi, A., Amor, H., & Hammadeh, M. E. (2017). Role of hormones in hypoactive sexual desire disorder and current treatment. Journal of the Turkish-German Gynecological Association, 18(4), 210–218. doi:10.4274/jtgga.2017.0071.

Chichinadze, K., & Chichinadze, N. (2008). Stress-induced increase of testosterone: Contributions of social status and sympathetic reactivity. Physiology & Behavior, 94(4), 595–603. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.03.020.

Marazziti, D., & Canale, D. (2004). Hormonal changes when falling in Love. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(7), 931–936. doi:/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.08.006.

Péloquin, K., Brassard, A., Delisle, G., & Bédard, M. (2013). Integrating the attachment, caregiving, and sexual systems into the understanding of sexual satisfaction. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 45(3), 185-195. doi:10.1037/a0033514.

Diamond, L. M. (2003). What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire. Psychological Review, 110(1), 173-192. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.110.1.173.

Emerging perspectives on distinctions between romantic love and sexual desire. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(3), 116–119. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00287.x.

Acevedo, B. P., Poulin, M. J., Collins, N. L. & Brown, L. L. (2020). After the honeymoon: neural and genetic correlates of romantic love in newlywed marriages. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00634.

Gander, M., & Buchheim, A. (2015). Attachment classification, psychophysiology and frontal EEG asymmetry across the lifespan: A Review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00079.

Botvinick, M. M., Cohen, J. D., & Carter, C. S. (2004). Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: An update. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(12), 539–546. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.10.003.

Maddock, R. J. (1999). The retrosplenial cortex and emotion: New insights from functional neuroimaging of the human brain. Trends in Neurosciences, 22(7), 310–316. doi:10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01374-5.

Winston J. S., Strange B. A., O'Doherty J., Dolan R. J. (2002). Automatic and intentional brain responses during evaluation of trustworthiness of faces. Nat. Neurosci. 5, 277–283. doi:10.1038/nn816.

Aron, A., Fisher, H., Mashek, D. J., Strong, G., Li, H., & Brown, L. L. (2005). Reward, motivation, and emotion systems associated with early-stage intense romantic love. Journal of Neurophysiology, 94(1), 327–337. doi:10.1152/jn.00838.2004.

Glover J. A., Galliher, R. V., & Crowell, K. A. (2015). Young women’s passionate friendships: a qualitative analysis. Journal of Gender Studies, 24(1), 70-84. doi:10.1080/09589236.2013.820131.

Suleiman, A. B., Galván, A., Harden, K. P., & Dahl, R. E. (2017). Becoming a sexual being: the ‘elephant in the room’ of adolescent brain development. Development of Cognitive Neuroscience, 25, 209-220. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2016.09.004.

Love, T. M. (2013). Oxytocin, motivation, and the role of dopamine. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 0, 49-60. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2013.06.011.

Czernecka, J. (2021). The social definition of love and its role in maintaining and intimate relationship: Typology of attitudes towards love. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Sociologica, (79), 121–132. doi:10.18778/0208-600x.79.07.

Moors, A. C., Gesselman, A. N., & Garcia, J. R. (2021). Desire, familiarity, and engagement in polyamory: Results from a national sample of single adults in the United States. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.619640.